ARTIST INTERVIEW: Marcos Carrasquer

Marcos Carrasquer

What inspired you to become an artist? When did you decide to turn your passion into a career?

Probably from the beginning, I mean being still a kid you experience reality in a non-passive way, observing the world with open eyes and curiosity, letting everything in, but at the same time, and that’s what I mean with non-passive - there’s that irrepressible urge to bend or adapt that reality, to make it your own story. In the beginning by trying to copy the things you observe but inside yourself you already know that by just trying to copy that thing on paper, it already is something new, something yours and it has gained his independence from the real material stuff. I loved to play football as a kid, but we lost too many matches to seriously consider becoming a professional player and at twelve years old I thought ok I will be a painter, that’s what I love most.

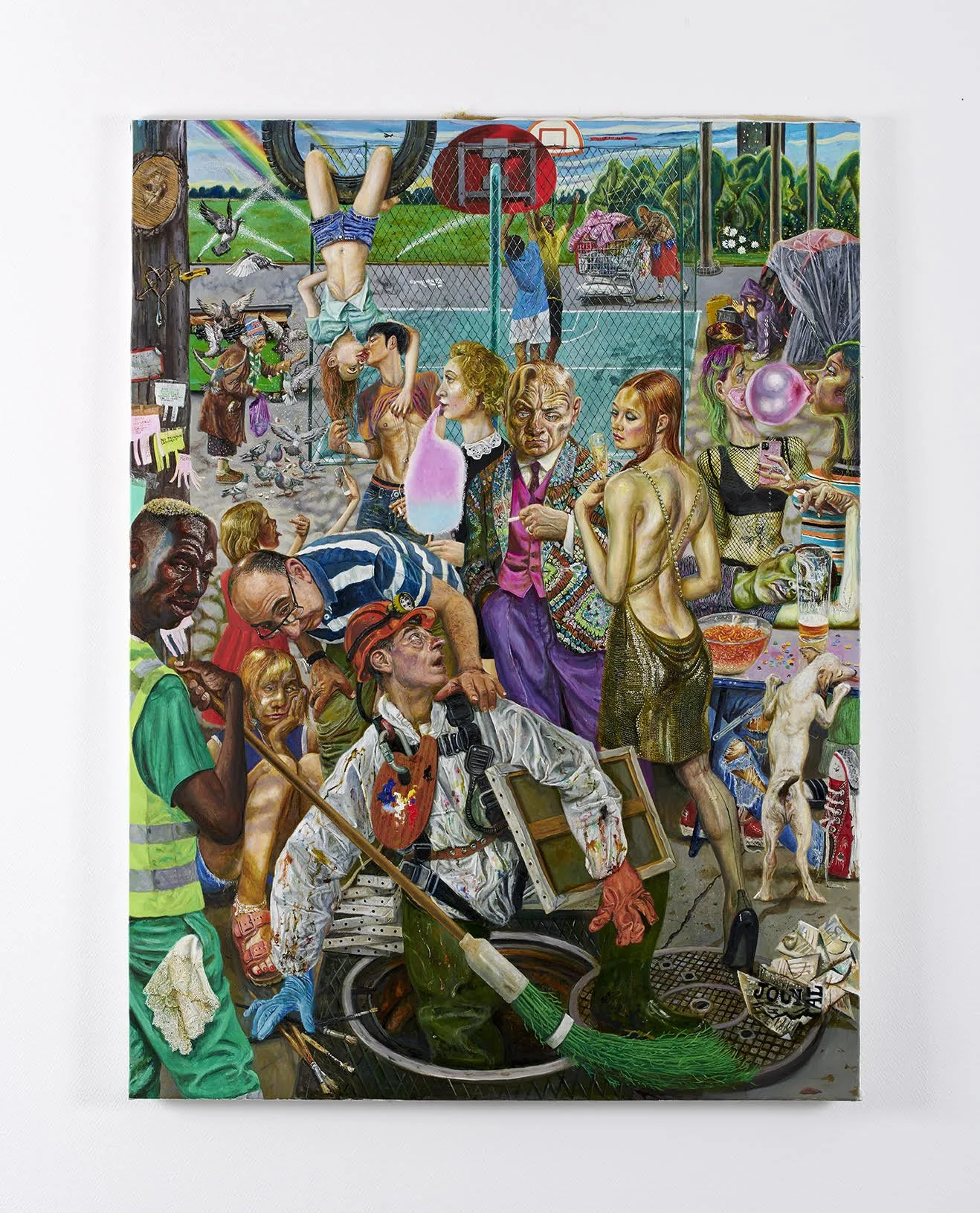

SOYONS TOUT

How has your family's experience with the Spanish Civil War been influential to your artwork? How do you echo the trauma and personal stories of your relatives in your paintings?

Ok - The Spanish Civil War has been a direct theme in some of my works and it is certainly a painful theme and very present all through my younger years at my parents home. It has been influential on my artwork for sure but other events have been too.. I’ve read dozens of books on the Holocaust for example, till exhaustion almost, I don’t think I could read any more books on that matter, it was almost obsessive and at the end I felt like the more I read the less I understood of what had happened. Same with the Spanish Civil War, I mean you know it ends badly, Franco wins at the end in all the books you read, in all the movies you see and we lose, it sucks. It’s horrific to see we learn nothing from what happened, from history, we’re still stupid and malicious, we’re guided by fear and cowardly pointing the scapegoats out of laziness and cowardice.

The core subjects in your paintings are people. Why do you find people fascinating to paint?

Because it’s the only thing I’m interested in, people. I look at other painter’s paintings of landscapes or cats for example, and I have no problem with that. A painting is never good or bad because of its subject. As a painter it is always a challenge to paint a face, a hand, a foot, it’s purely formal fun and besides that, my paintings and drawings deal with people, our relationships, confrontations, battles, histories etc., it’s what I want to paint, our contemporaneity. I made a painting called ‘Democritus and Heraclitus’, who were two Greek philosophers. Heraclitus is the "weeping philosopher", as opposed to Democritus, who is known as the "laughing philosopher". Weep or cry as a reaction to the folly of mankind. And well, I guess I’m part Heraclitus because life is tragic by nature, it ends up in death and l’m part Democritus because laughter and irony is vital, we can’t handle it without. So I’m driven by curiosity, people fascinate me, what they do, how they think, trying to get in their skin, figure out how they carry themselves, trying to avoid to judge them, though sometimes this is difficult, especially with soulless power freaks and narcissists, politicians and billionaires.

Democritus and Heraclitus

When did you initially start exploring social issues in your work? Are any of the scenes you paint ones which you have pictured in real-life? Or do they stem from your imagination?

They stem both from real life and imagination and coexist in the same painting. I like to work in an anachronistic way mixing periods of time and situations, in different layers of perception, I mean I don’t really like to stand next to my painting and say, “This is a painting about refugees and that is a painting about social injustice.” it doesn’t work that way, it’s not a press cartoon, although press cartoonists were definitely a major inspiration when I started as a kid. The social issues, as you say, have always been there, it’s what I want to paint about. The issue, the subject is the starter and from there on, the image; its iconography, its composition, its colours, take over and I try to make a strong image, not an illustration of an idea.

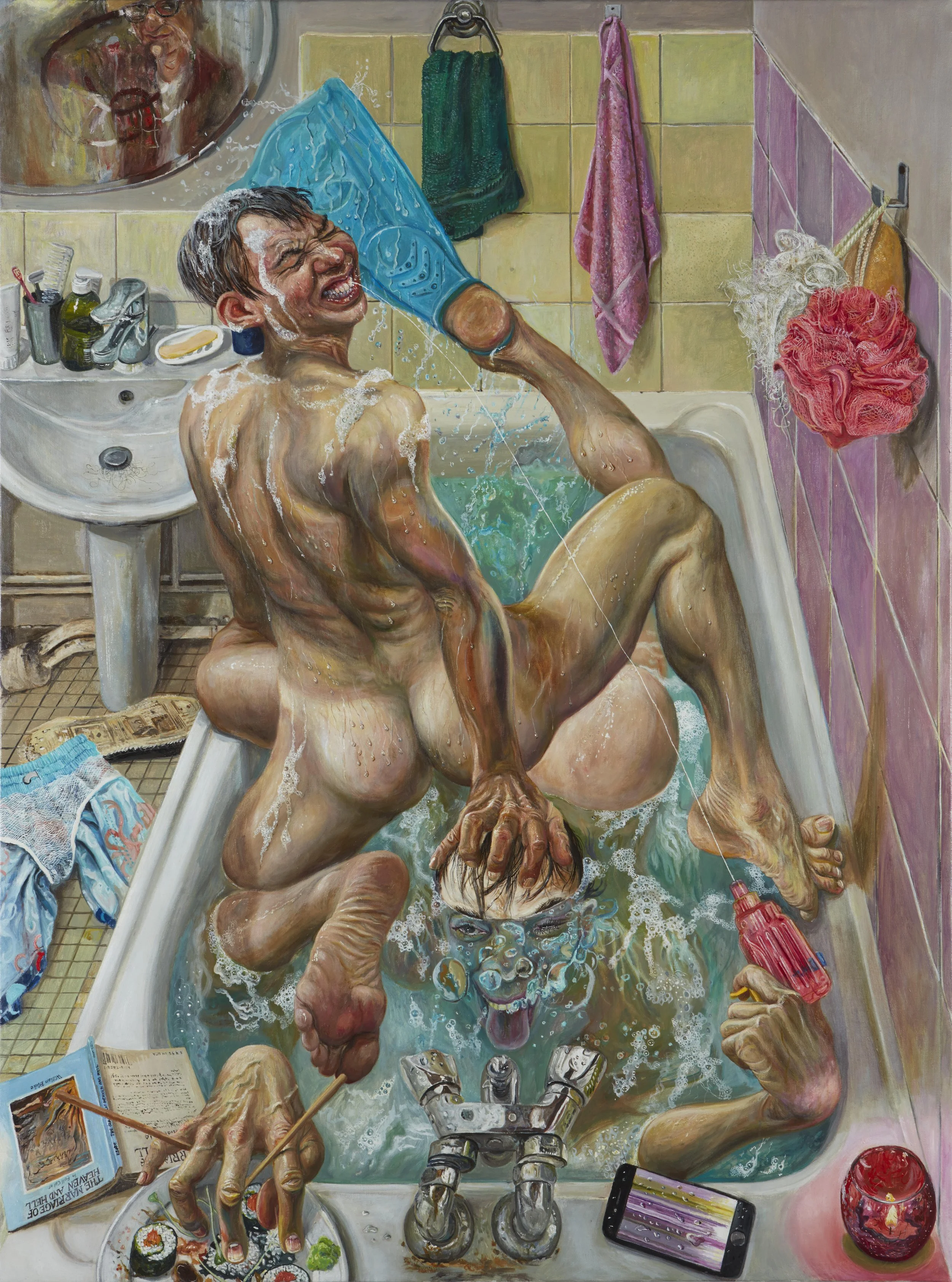

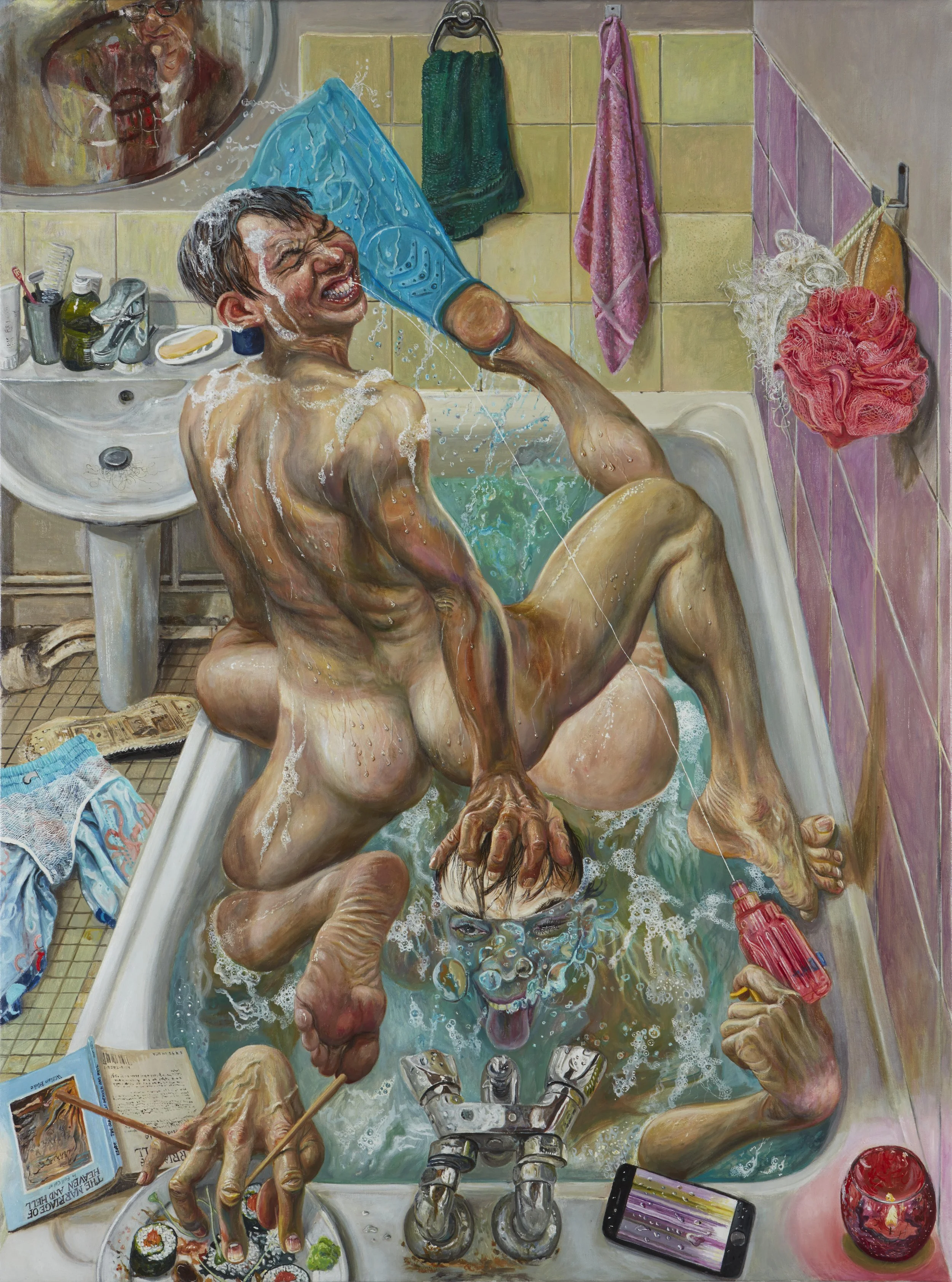

La Déchéance

What originally sparked the idea to create the piece 'Under Your Skin'? What is the narrative behind this piece?

I wanted to make a painting about the artist, the painter in this case, and his ‘role’ in society. You see a painter -who bizarrely looks a bit like me, coming out of a sewer hole bearing paintings under his arm supposedly painted underground, in the sewer. On the surface, the man in the striped polo shirt; who has some resemblance with my gallerist, receives the painting empathetically and there seems to be some kind of vernissage organised to welcome the underground paintings. A socialite couple holding champagne glasses are boringly attending this open air opening, a junky has fallen asleep at the Cheetos bowl table and the rest of the people are just carrying on with their lives, not really interested in what the painter has seen under the world’s skin and has come to show. It’s a tragicomic allegory, of course, on art and society. The painter tries to show what’s under the surface, under the superficial and not everybody is particularly impatient to witness that.

Under your skin

Thinking about your last piece, describe your process from start to finish. What sparked the initial idea for the piece?

The painting is called Unfinished. What sparked the initial idea was a picture I saw on internet of Lucian Freud’s last painting left unfinished when he died. And then I thought he must have been pissed off by not finishing the painting and then I thought he would have liked to come back from the dead to finish it. So I painted myself in a coffin, the viewpoint in the painting is thus from the man in the casket, it could be me or it could be the viewer who looks at the painting and this person is looking up at three persons looking down at the person in the coffin, drinking champagne and smoking cigarettes and one woman’s hand throwing a rose in the casket during the funeral reception. I thought it was funny to make a painting from a dead man’s viewpoint. Afterwards, during the painting process I added some details that popped up in my head, like the small fly or the post-it on the wall that says ‘Бога Нет’, There is no God in Russian, which I took from a Soviet poster where you see a cosmonaut floating in space who pronounces this phrase, as if he had checked the entire cosmos for divine presence and not having found anything. I think that’s funny too and decided to put it in the painting. Originally this painting was also a commission to appear on the cover of Grosse victime magazine, a great fanzine published in Paris. The guy on the left of the painting is Antoine Paris who runs that fanzine and asked me to do the cover.

La Déchéance

You have stated in a previous interview that you write a list with your ideas for future paintings. What was the last idea on your list?

I’m never sure when I write it down if I’m actually going to paint it and normally it’s just two or three keywords and the last note is Smash/rage room Ludd. I didn’t know they existed these rage rooms where people with helmets and protection gear equipped with sledgehammers, smash computers, printers and other objects in order to de-stress. Very interesting. And I added Ludd in this note in historical reference to late 18th century legendary Ned Ludd who is said to have destroyed knitting frames in Leicester; machines that were replacing the weaver’s manual work. So there’s the parallel between the Luddite movement at the beginning of Industrial Revolution and a bunch of stressed managers who smash machines to decompress and at the same time there is AI which is in a way a contemporary knitting frame destroying manual labour. A painting will come from this I guess.

How do you picture your work evolving in the future?

I really don’t think about that too much. I start a painting, finish it and start a new one. Of course it develops, there’s always something new, some changes but it’s all intuitive, not planned. I don’t work in series, I don’t make series or a concrete theme for one particular show and then come up with another theme. Looking back at what I’ve done so far, I see that things have happened, that things move but there’s not this or that ‘period’ l don’t know, I just hope I can continue painting for many years until they put me in a casket, and why not beyond that.

You are here

Why do you think art is important in society?

I’m not sure it is. I know it is for me. I’m not really sure a lot of people consider painting important in their lives. It’s different with music, everybody loves music, there’s all styles of music for everyone, I could not live without music, it’s hard to imagine anybody could. Music has another sensoriality. But painting is eternal also, the cavemen painted and we’ve been painting ever since. But art is not adjustable in society no matter how much politics has tried to do so. Art is not really functional, besides architecture and of course a world without art is unimaginable, so I don’t even consider it. The need to bend reality, to embrace it, to understand it and in consequence turn it into an artefact, into something new, like I said in the beginning of this interview, will always be a reality.