ARTIST INTERVIEW: David Cobley

David Cobley

Tell me about yourself. What sparked your interest in painting?

Well, I grew up in a typical family in a little town at the heart of the boot and shoe industry in Northamptonshire. I and my younger brother had a very happy childhood there. We went to the local school and did the sort of things most children do, like riding a bike, playing in the street with friends, and exploring the woods and fields nearby.

I liked drawing and had a lot of encouragement from those around me, but owe a great deal to one particular uncle, whose comment ‘you could be rich and famous one day’, made me think I might be able to paint the sort of pictures I was beginning to come across in books that came my way.

Some of those pictures were by the Old Masters. I was fascinated by the way they were able to use paint to create the illusion of three dimensions on a flat surface. They had a grasp of anatomy based on hours of observational drawing and a mastery over their particular medium, which enabled them to create dramatic compositions that fired the imagination and would stand the test of time. I was particularly drawn to Rembrandt. His paintings had a psychological depth that made a big impression on me, and a print of his Self-Portrait as the Apostle Paul, hung on my bedroom wall as a reminder of the direction I wanted my life to take.

What do you find fascinating about the human face? How do you capture a likeness through portraiture?

As babies, we are totally dependent on our mother for everything, and hers is the first face we recognise. As we develop, the faces of other family members and friends become important. Their facial expressions, combined with the sounds they make, help us understand what they are thinking and feeling. Faces are a window on the life within.

I remember as a young boy wondering what it might be like to be someone else. A relative of mine had a finger missing. A family friend was blind. On old man opposite me on the train had a tear in his eye. I used to imagine what it would be like to be them.

Capturing a likeness is based on one’s ability to draw. It’s largely a mechanical process that combines a sculptural grasp of what one is observing with the assessment of angles and distances between features. As with anything, constant practice is essential.

Capturing the ‘essence’ of someone in paint on canvas is more complicated. I’m not sure it’s possible. For anyone painting a portrait it’s the holy grail, but no matter how hard one tries, is always tantalisingly out of reach.

You have painted many public figures. Who have you enjoyed painting the most and why?

My work has given me access to a huge variety of people, each inhabiting a world very different to my own. Lord Mayors, Members of Parliament, members of the Royal Family, Supreme Court Judges, headmasters, actors, scientists, comedians and so on. Every one of my sitters has been totally unique and I have thoroughly enjoyed the time I have spent with them.

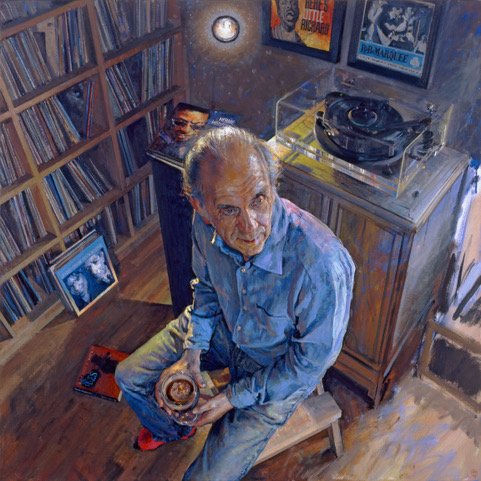

Painting Trevor, the subject of Blues, Beer and Rock ’n’ Roll, was particularly enjoyable. Sittings took place in his music room, where he listens to the records he has acquired over the course of a lifetime on a traditional turntable. While I painted, we listened to music and chatted, and at the end of the day enjoyed a nice glass of beer together. It doesn’t get much better than that!

Blues, Beer and Rock ’n’ Roll

Has there been a conversation with one of your sitters that has stuck with you?

It wasn’t so much a conversation as a phrase uttered by mistake. Ken Dodd had allowed me into his dressing room to do some drawing and take photos, and we were chatting during the interval. As he stood up to return to the stage, tickling sticks at the ready, I wished him luck before realising this was this was the last thing one says to a performer. I immediately corrected myself with “break a leg!”, the customary verbal encouragement on such occasions. Who knows what might have happened in the second half if I hadn’t!

How do your paintings reflect you as an individual? Would you say you’re quite observant of your surroundings?

My art master used to say every painting is a self-portrait. He also used to say most people walk around with their eyes shut. That’s an exaggeration of course, but some people are definitely more observant than others. We all observe the world though our own unique pair of eyes, and those observations are coloured by our own unique experience of life. I notice some things but not others. Cars don’t interest me, so I tend not to notice them unless they are obscuring my line of vision. On the other hand, I am fascinated by what people do and how they go about it. I notice what they are wearing and the way they behave. It’s a question of focus I think.

Are there any common themes/ narratives throughout your work?

Rather naively, I have wanted my work to make a difference and to somehow make the world a better place. Ah, the misplaced idealism of youth!

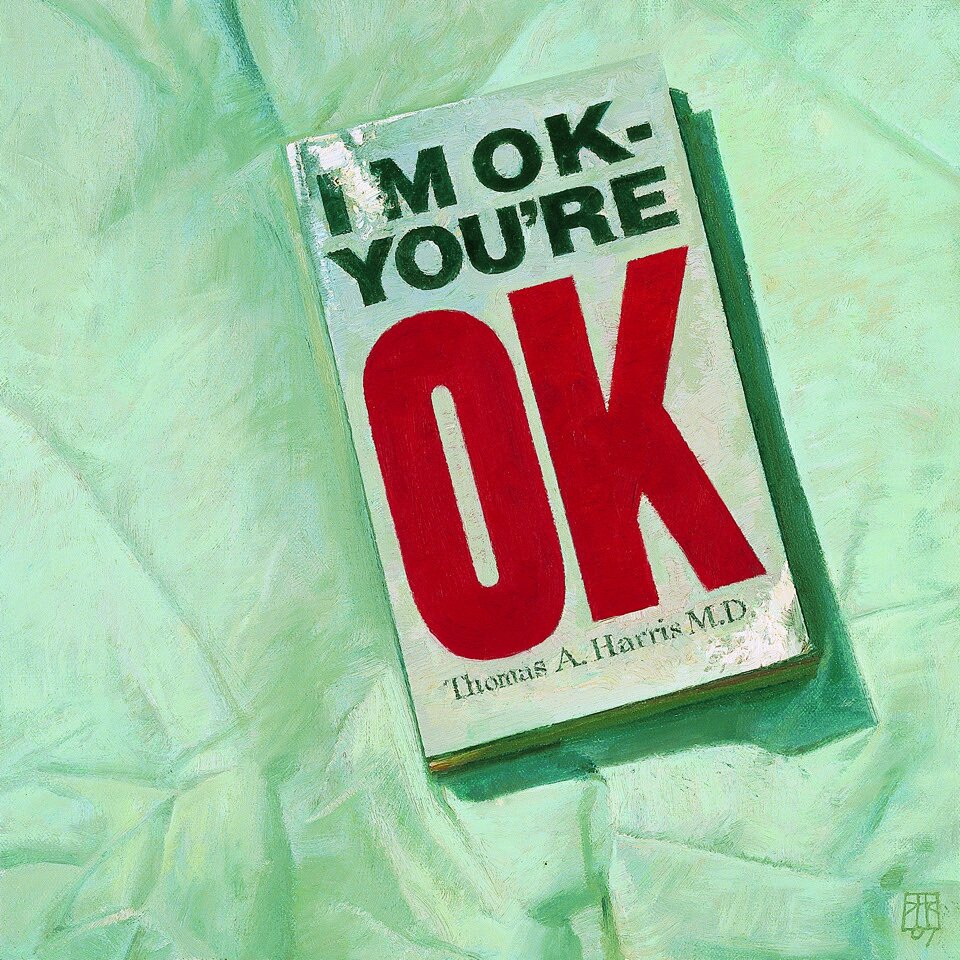

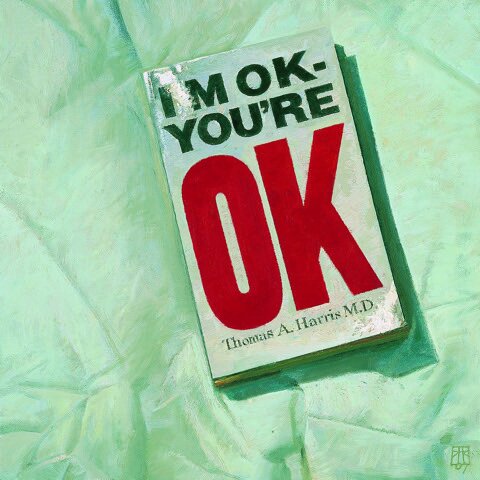

I am in the fortunate position to be able to paint whatever I like, however I like. One day it could be a landscape, the next an abstract. If there has been a common theme, it is people and the way they behave towards each other and the environment around them. Some years ago I came across the book I’m OK You’re Ok. You don’t need to read the book - it’s all there in the title.

I’m OK You’re Ok

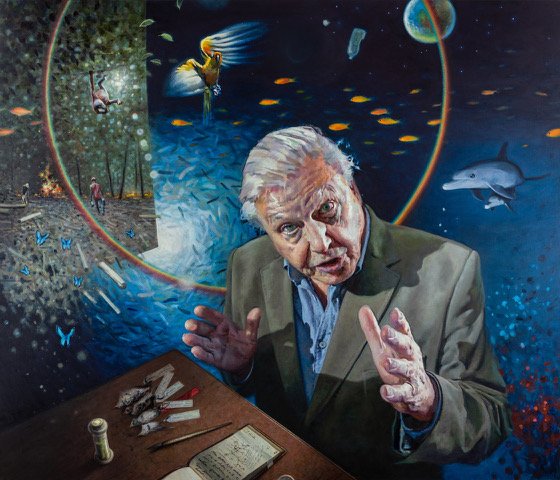

Thinking about your portrait of Sir David Attenborough, describe the process for creating this piece. How did you feel when you were commissioned to paint this piece? Do you ever feel pressure when you’re painting a high profile sitter?

I hate the idea of celebrity. We are all celebrities in a way. You are a celebrity, I am a celebrity. We have the starring role in our own particular soap opera, mini-series or feature-length film, and are at the very centre of our own very special universe. I treat every painting as important as the next, whomever the subject might be.

As soon as I heard the BBC was thinking of asking me to carry out the commission, I did everything I could to get it. I dropped what I was doing to trawl through hundreds of photos and videos of him online, looking for something that showed him communicating his knowledge and enthusiasm for the natural world. By the following morning, I was able to send Annabel a couple of mockups to show the BBC what I thought might work.

I met Sir David at his home in Richmond with Robert Seatter, Head of BBC History, in early 2019. We were there for a couple of hours. When you speak to Sir David he looks you in the eye and listens to you with great intensity - as if you were the only creature left on earth after a major catastrophe! I had a camera with me and took one or two photos of him inside the house and in the garden. I suppose I already knew that I would be basing my portrait on images of him already out there on film, so it was more to record my visit. It was the only time I had with him until the unveiling at Broadcasting House.

I would have surrounded him with every one of the animals, plants and insects he has brought to our screens if there had been room. It was important to have at least one creature that was representative of the air, of the land and of the sea. The orangutan seemed particularly important, as the logging of ancient rainforests has had such a devastating impact on its habitat, and because we are such close relatives. The same forests are also home to the brightly coloured Sun Conure - its posture suggesting it has been startled by the fall of another tree nearby.

Read more: https://www.mallgalleries.org.uk/about-us/news/painting-sir-david-attenborough-with-david-cobley-rp

Sir David Attenborough

Tell me about a typical day in your studio. How does the space you have created inspire you?

Every day is different and these days I can generally please myself. If I don’t feel like working, I do something else.

I have had many studios over the years, but the current one is a ground floor flat in the middle of Devizes with a north-facing window. Last year I redecorated it and had new lighting installed so that I can work in artificial light if it’s dull outside. I have everything I need there and know where something is when I want it, which hasn’t always been the case! So, it’s practical rather than inspiring. My inspiration comes from elsewhere, but it’s nice to have everything at hand.

Coffee time in situ

Which painting has been your favourite to work on and why?

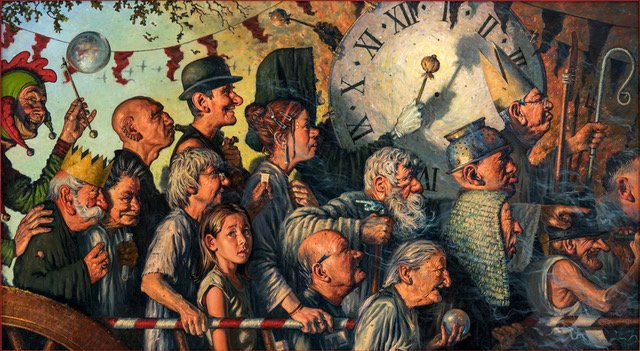

There are one or two I have particularly enjoyed, but Bandwagon to Oblivion is certainly one of them.

It could just have easily been called ‘The Road To Nowhere’ or ‘The Blind Leading The Blind’, had those titles not been used by others before me. I painted it when I was feeling particularly pessimistic about the future of the human race, but tried to instil it with a sense of the comically absurd to make it more palatable.

The characters depicted are almost caricatures, but are all based on real people. In 1995, I was working on a group portrait of staff members at the The National Society for Epilepsy at Chalfont St Peter. Some of the residents there had particularly interesting features, so I asked Professor Shorvon, the Medical Director, whether I might take photos of them. He agreed, and each of them sat for me individually by a lamp I had brought with me. Back in the studio, I worked from a mannequin dressed in a variety of costumes and headgear, and in combination with the photos managed to piece together the final composition.

The wagon is a kind of metaphor for the world in which we find ourselves and from which we cannot escape. Each person clings to something that they desperately believe will carry them through the impending disaster, but each one is deluded. I am egging everyone on as the jester on the far left left, while the little girl in the foreground is the youngest of my three daughters - the only one who seems to be the least bit concerned about where we are all heading.

Bandwagon to Oblivion

What has been your greatest achievement so far as an artist? Have you endured any challenges?

Well apart from painting Sir David, I staged a solo exhibition at the Mall Galleries in 2019 to help launch the book David Cobley: All By Himself. There were almost 200 drawings and paintings in the show, some of them more than six feet across. It was a kind of retrospective, and included a self-portrait painted when I was 18.

As for challenges, dropping out of art school to join the Moonies and finding myself in Japan 10 years later without a painting to my name was a sobering experience. Embarking on a career as a painter at the age of 30 with a young family to support wasn’t easy, but being away from painting for so long meant I had the impetus to make up for lost time.

Why do you think art is important in society?

‘Art’ is an abstract concept and almost impossible to define, so I’ll restrict my answer to the visual arts, and more especially to the specific area of painting and drawing.

I’m not sure how important it is. It would be an interesting (although totally impossible) experiment to remove all the paintings, drawings and prints from the world for a week and see what reaction it caused. Gallery owners and staff would probably be the first to notice the difference. Almost everyone has a picture on their walls that could loosely be called ‘art’, so we would all be affected to a lesser or greater extent. To continue the experiment for a year would be even more interesting. I imagine there would be an outpouring of creative activity, perhaps by people who had never picked up a pencil or paintbrush since they were at school, in an effort to replace what was was missing.

I know that as far as I’m concerned, painting and drawing has been a constant thread throughout my life and has led me in some very interesting directions. I still ask myself whether what I do has much significance, but I imagine I will always be making something. Whether it’s art or not, it really doesn’t matter.