ARTIST INTERVIEW: Will Taylor

Tell me about yourself. Your original career path was not in art. What was it that inspired you to become an artist instead? Have you always had a passion for art?

I have a sciences and engineering background, that led to a first career in business consulting for oil companies. I was lucky to be able to leave that career by choice in 2001, with only a strong feeling that I could do something completely opposite; working for myself outside a business environment. It is only looking back now that I can see connections between these two worlds, such as the importance of creativity. Many years ago, I had some engineering draughting training (but no formal art training since) and the basic learnings such as “lettering should be drawn, not written” are still helpful. Turning the wheel of a beautiful intaglio press and the smells of a print studio have a strong connection to an engineering workshop.

I look back at my Art A-level qualification that I did in 1981, and think how weak the work was in comparison to equivalent student work today - but “putting lines on paper” has always been there for me.

As an artist, you use a variety of mediums throughout your work. What do you enjoy about each medium? How does your choice of materials relate to the mood/feel of the piece you’re creating?

I would like to be an artist who is inspired by a subject and is able to use the best medium to capture and convey that image or thought, rather than be the master of one technique looking around for subjects that work best for it. I realise this is a somewhat endless challenge, but it helps me to keep on learning and moving forward. Ken Howard once advised me to “keep drawing for as long as possible” – meaning that one should not be tempted to settle too early on one painting technique or genre that sells and keep on repeating it.

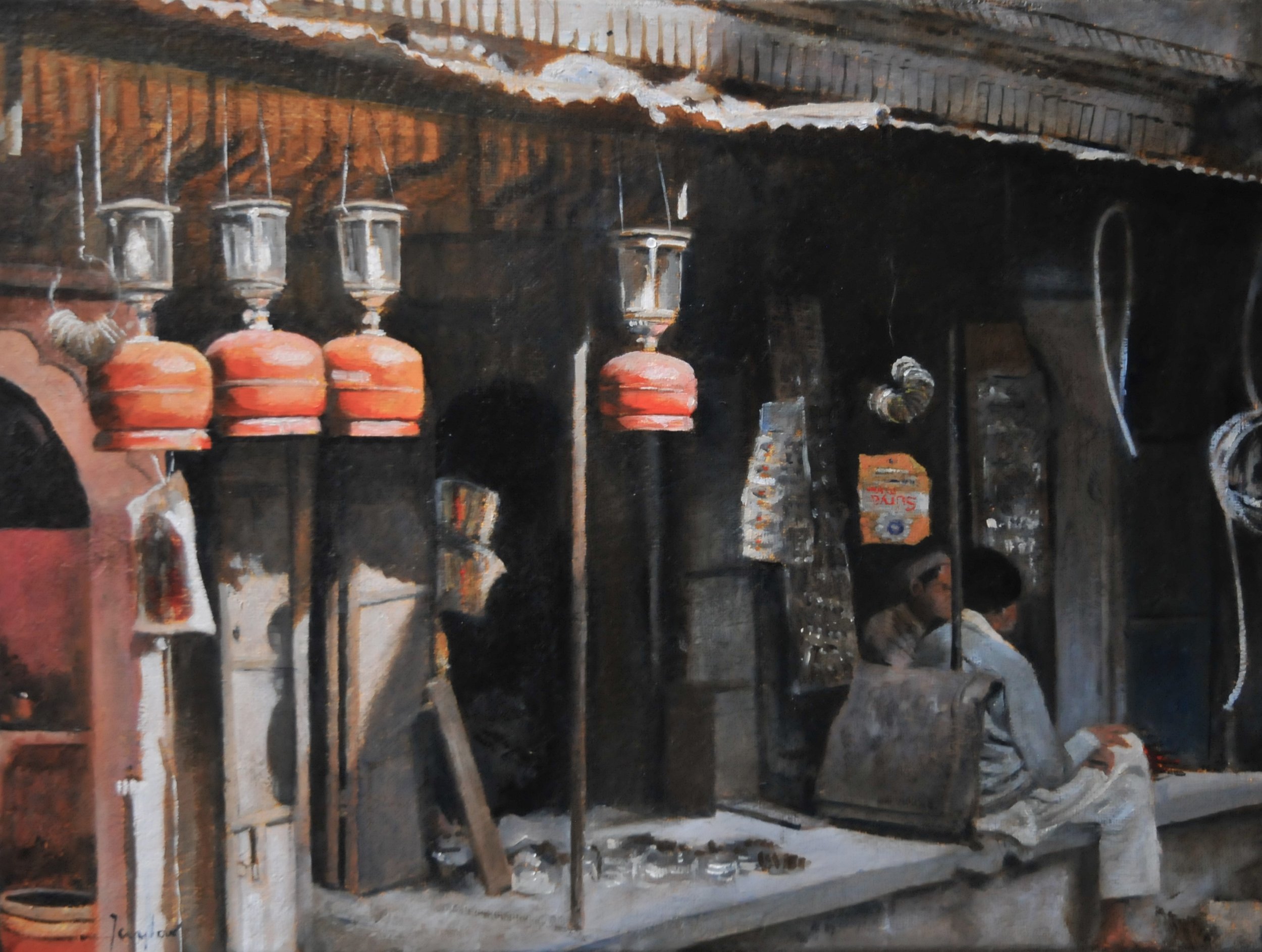

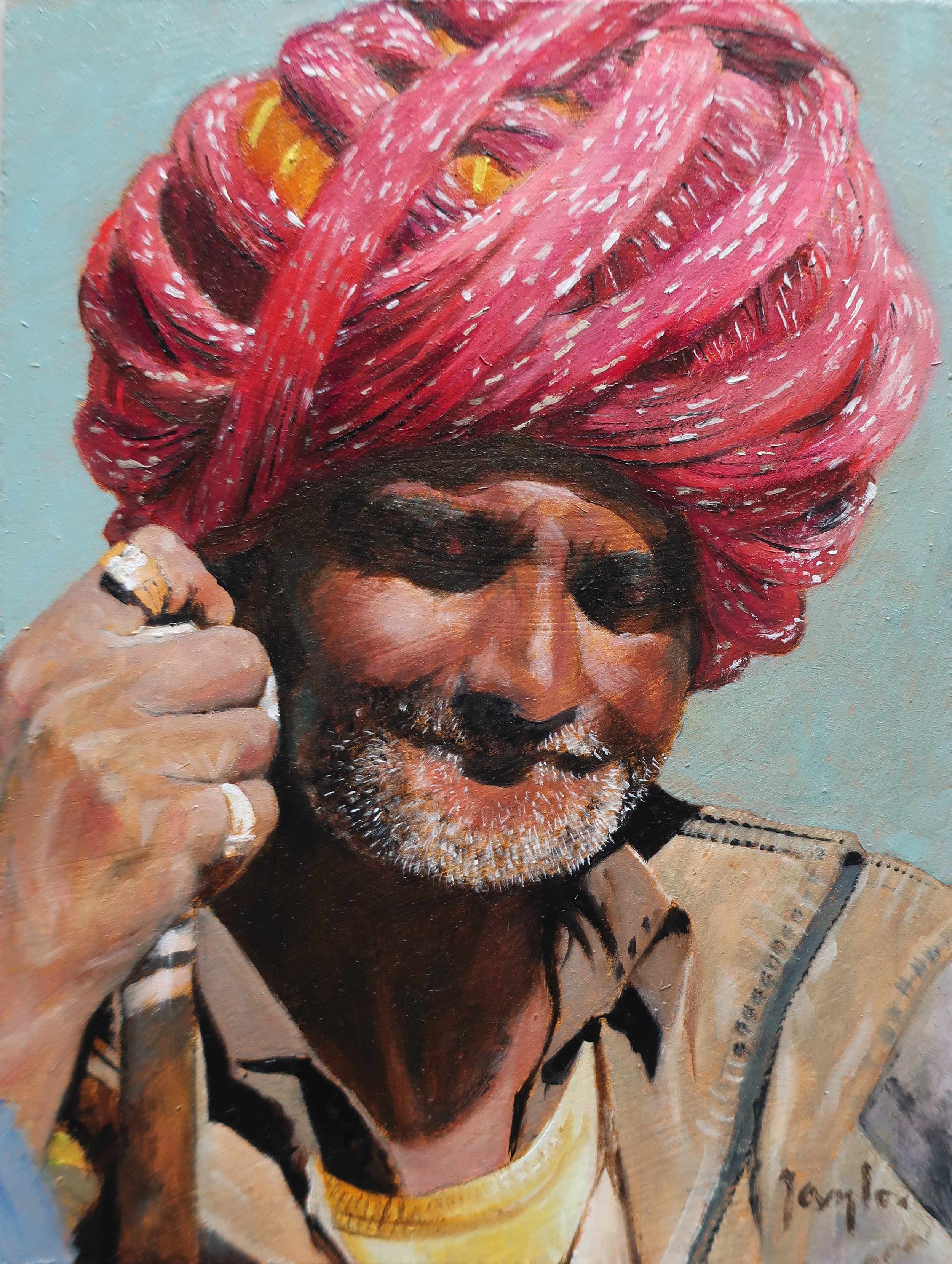

Etching and drawing with a needle remains at the core of what I do and I love the technical challenge. Large scale charcoal drawings are in a way a preparation for this, by exploring tones and drawing from the shoulder as an antidote to detailed line drawing. Oil painting allows exploration of colour palettes for the same subjects and I present them in the same scale and framing as the etchings, often using a limited (Zorn) palette. In the same way that my idea of a good etching is “all about the darks” (contrast this with a painter’s “inspired by light”), I love a small, dark, miserable, traditional technique of oil painting.

Your work depicts a range of subjects. However, a vast amount of your work depicts animals and nature. What do you find fascinating about these subjects?

Sometimes composition, contrast of darks and lights and mark-making seem more important than the actual subject matter. A work depicting sheep in a field may really have started out as a picture of a field. It’s as if the animals just wander in. Even the large charcoal animal drawings are a play on portraiture, as if the animal has accidentally nosed into a photographer’s studio.

A series of etchings inspired by Leonardo’s notebooks, started with science and language of ideas but ended up being populated by hares, sheep, mice, etc… It is left for the viewer to decide what the connections may be. One that is clearer is “Fibonacci’s Rabbit”, as the work on the Fibonacci sequence was based on rabbits.

Where do you find your inspiration? Is there anywhere you go that makes you feel particularly inspired?

The etching tradition really leads one to topographical subjects. I am lucky to have travelled to inspiring places in India and Morocco, as well as around Britain and Europe.

I have never thought of myself as a landscape artist, but I have recently moved a short distance to Romney Marsh. Once described as “The fifth continent”, the extraordinary skies over the flat landscape stretching to Dungeness, are a new inspiration for both working environment and subject matter.

Focusing on your etching series, what is your process for creating one of these pieces?

Carl Sagan once noted “How do you make an apple pie? – Well, first you create a universe”. So an understanding rather depends on where you start describing the process.

It is perhaps easier to describe what I don’t do: I tend not to use aquatint to create tones, I prefer traditional line and cross-hatch. I don’t use a master printmaker and print the editions myself in my own studio in relatively short runs. I don’t use coloured ink, I love the colours implied by a single wipe of sepia.

Is there an artist that you particularly admire? If they were sat next to you right now, what would you ask them?

Griggs: “Cheer up, and tell me more about the English landscape before the Great War”

Sargent: “Got any tips?”

Caravaggio: “Could I ask you to move, please”

What might surprise someone about your work?

People remark on how detailed my work is. They would be surprised to learn of how much effort I expend on eliminating detail and trying to make it look effortless.

Out of all your work, which piece are you most proud of?

I am very proud to have two etchings in the Victoria & Albert Print Collection. I was at Imperial College in South Kensington and much later an exhibition, “Impressions of the 20th Century”, in the old Boiler House Project was quite formative in my learning of printmaking. One of my V&A pieces, “Waterloo Sands”, is of the Mersey estuary at Crosby where I grew up.

What has been your biggest achievement so far as an artist? Has there been anything you have found challenging?

I would worry if there was a piece I was working on that wasn’t challenging in some way. It would mean that I was not exploring and learning all the time. My achievement so far has been to be a working artist longer than I was in my first career.

Why do you think art is important in society?

Creativity is as the core of humanity and is central to our sense of self and sense of freedom. The current debate about the nature of Artificial Intelligence and the role of creativity is important. Human creativity must surely be key in differentiating us from our computer creations.

At a practical level, I was asked to give a print-making tutorial to school-age children looking for art scholarships. I noted to them that even if they did not like filing metal plates, putting their fingers in etching acid, turning a heavy press wheel, or never came across etching ever again, as long as they could remember and describe even a few parts of the intaglio printing process in their scholarship interview, (or even university or first job interview) it would: 1. Show independent learning and initiative

2. Impress that they could remember an elaborate process

3. Demonstrate they have tried something rather interesting and out of the normal. It worked.

![Cow [No.31] Charcoal on paper 56 x 76cms Will Taylor.JPG](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/63c7c3624dafd37ad0641b1f/1684777341745-YHGB4L7UKNTOFG7YE98F/Cow+%5BNo.31%5D++Charcoal+on+paper++56+x+76cms++Will+Taylor.JPG)