ARTIST INTERVIEW: Lukas Leisinger

Lukas Leisinger

In 2024, you graduated from the prestigious Chelsea College of Arts. When did your love for creating art begin? And when did you establish THAT you wanted to pursue a career in art?

Creating art has been a space of comfort for me. I’ve always loved drawing since I was a child, but I only started painting at 16 years old. I remember when I was at school, my teacher acknowledged my talent for drawing but told me I ‘couldn’t paint’. I started copying historical portraits and, over the years, continued to develop my painting technique through copying old masters like Rubens and Van Dyck. After secondary school, I decided to continue my education down the avenue of art, fuelled entirely by my love for it, not with any view of career prospects. I wasn’t particularly conscious of what a career in art meant, probably until the end of my first year of university at Chelsea College of Arts. Seeing other brilliant contemporary painters exhibiting and being recognised for their talent and vision really confirmed to me this is what I want to be doing.

In your biography, you state you’re ‘fascinated by the idea of nostalgia’. Why is this? How is this communicated in your work?

I’m fascinated by nostalgia because it’s never just a clear memory; it’s filtered, warped, and often romanticised or even misremembered. That unclear distance between what was and what’s recollected opens up a space of ambiguity, which is central to my work. I often work with found images, old home videos, archival material, old magazines, not because I have a personal connection to them, but because they evoke a kind of universal familiarity. They feel like they belong to someone, but not quite to me. That tension creates an eerie intimacy, which I push further in the painting process, obscuring faces, distorting or scraping away details, and placing figures in half remembered or liminal environments. By manipulating these images, I’m not trying to recreate a specific memory, but fabricate one to explore how the emotional weight of nostalgia can be manufactured and how the viewers of my paintings may also feel that weight.

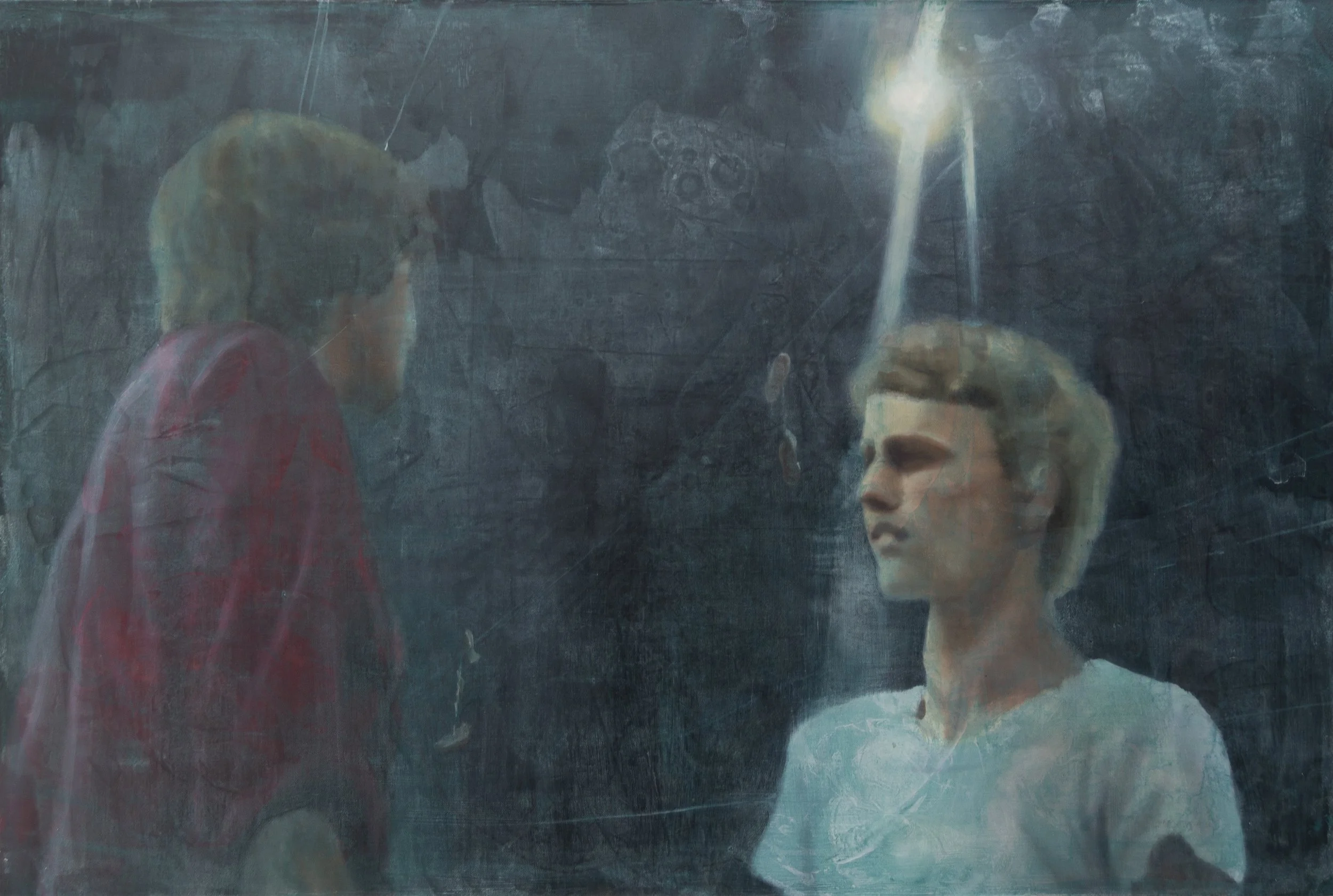

‘The Nightlight Stays On’

Thinking about your latest piece, ‘Moths to a Lighthouse’, what sparked your imagination to paint this? Describe your process from start to finish of this painting.

The process of ‘Moths to a Lighthouse’ began how all my paintings begin: in Photoshop. I start by experimenting with my collected imagery, collaging figures onto environments. I had a brilliant photograph by William Klein of two rather embarrassed businessmen walking out of a massage parlour. Not wanting to directly reference his work, I had to make some changes to the figures. I absolutely loved the device of obscuring the face by shielding it from the camera. This mechanism of obstruction of identity helps create distance between the figures and the viewer, adding ambiguity and unease. The background is of a photograph I had taken of a footpath I use frequently in the village where I grew up. I sketch in my underpainting and, layer by layer, work up the painting to a finished and refined point. Next is the riskiest part of the process: I put a wash of white paint on top to add a fog and another level of obstruction between the viewer and the scene. This can, and has, gone wrong, and I was especially cautious with this painting, given its large scale.

‘Moths to a Lighthouse’

How does your signature blurring technique assist in conveying the narrative throughout your work? When did you adopt this technique?

In my paintings, I like to have an ambiguous narrative. This is to highlight the veiled nature of nostalgia but also to allow the viewer to project their own interpretations and memories onto the image. My blurring techniques usually add another layer of distance and obscurity to the painting. It also allows me to obscure certain details I want to hide from the viewer. All of this helps emulate this idea of recollection and nostalgia, and the uneasy feeling that accompanies it. I’ve experimented with different techniques of veiling the more figurative elements of my work. The wash I put over the top of my paintings has proved to be the most successful, adding a fog between the clarified scene and the viewer.

‘A Host of Phantom Listeners’

What is your favourite part of your painting process? Which is your least favourite part?

I would have to say my favourite part of my painting process is starting with a blank canvas and just getting paint down. The initial excitement of sculpting the image in and seeing it come alive is always a brilliant feeling. My least favourite part of painting is perhaps nearing the end of a piece; refining details can become very monotonous.

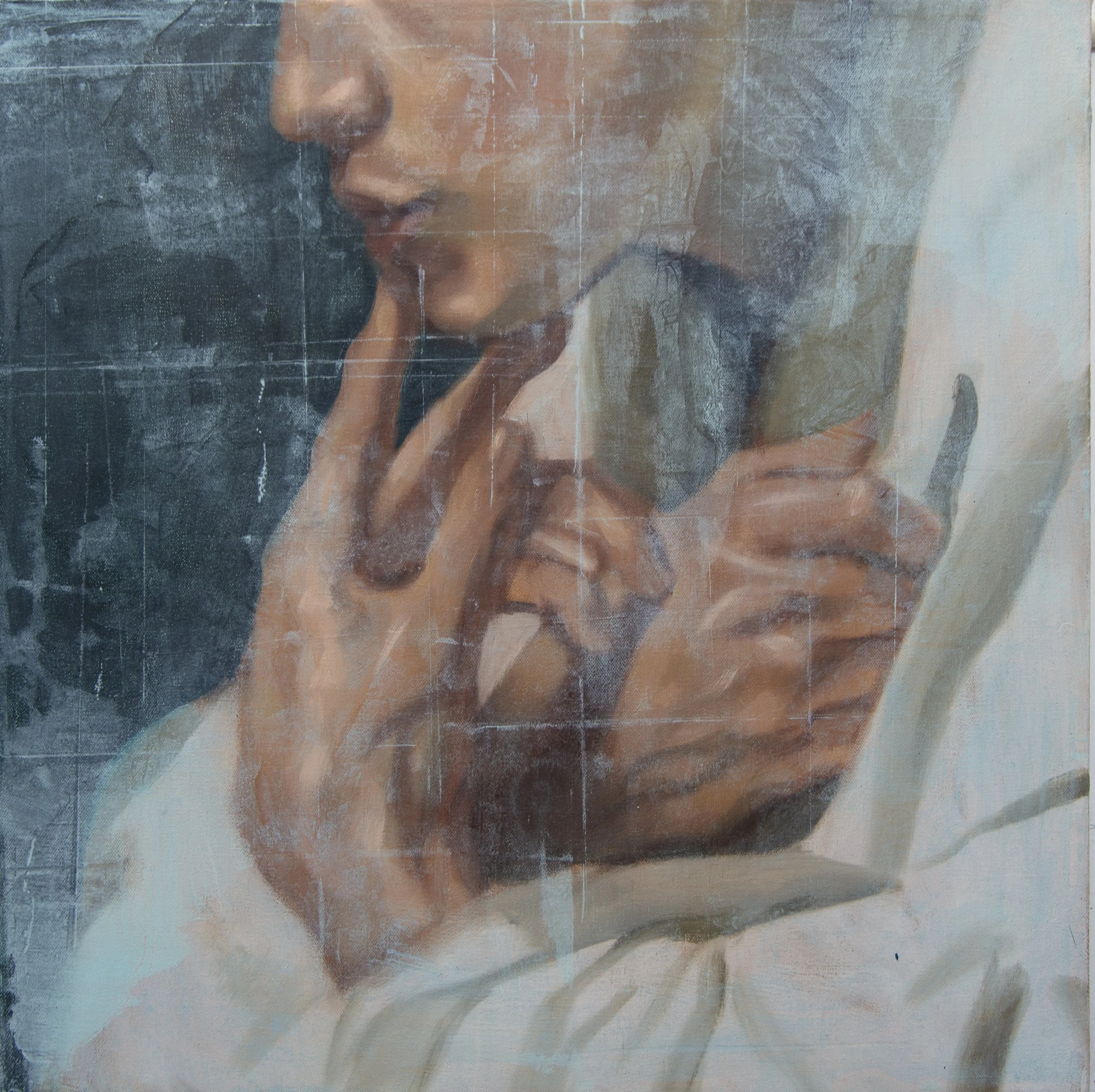

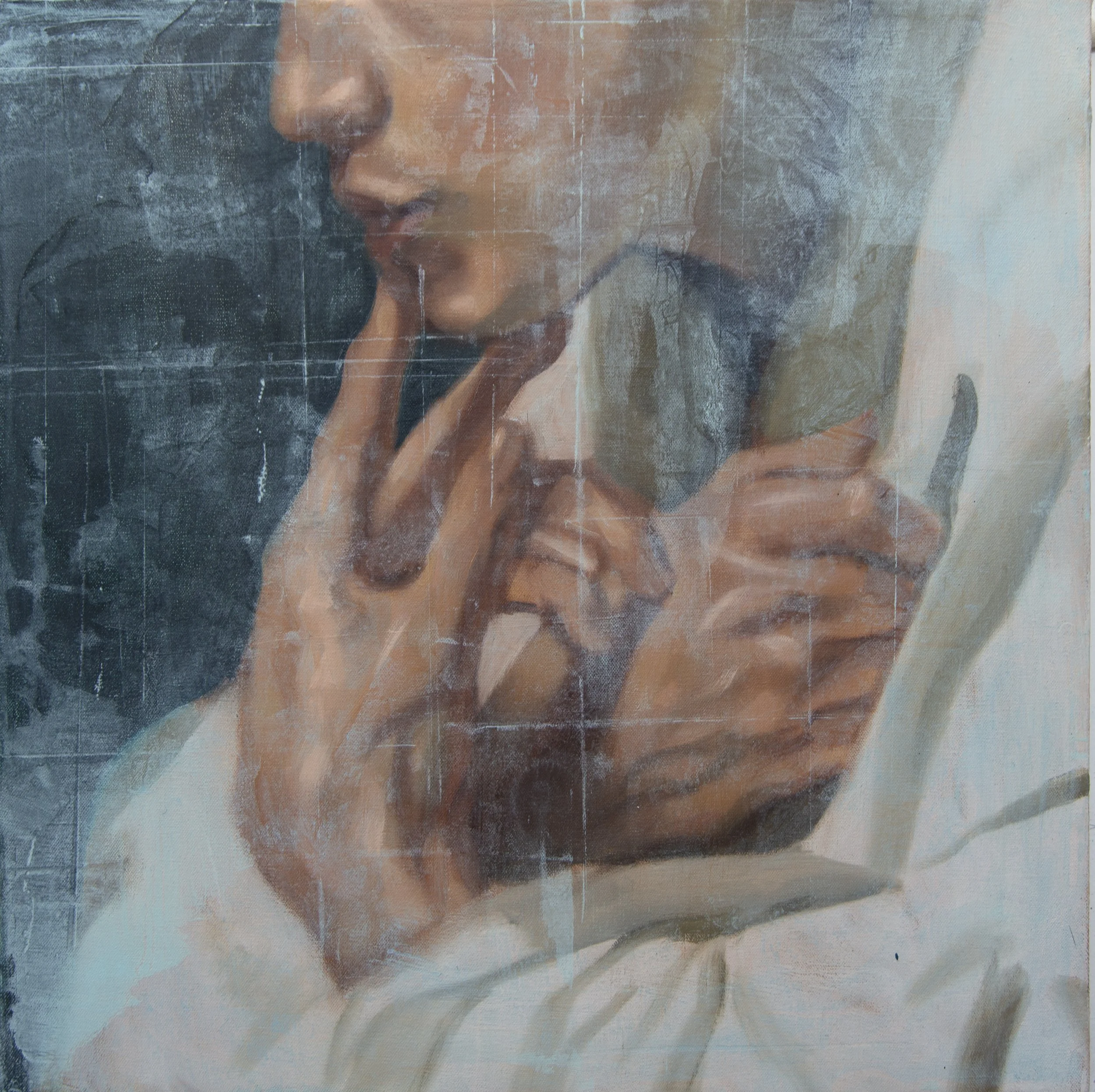

‘Splinters’

People are mostly the main subjects in your artwork. What fascinates you about the human form? Why do you feel compelled to paint it?

I’ve always been drawn to painting people. The human body is the greatest storytelling device image-makers have. The smallest gesture or pose can suggest a certain mood and guide the viewer’s emotional response. I use the figure as a kind of vessel for ambiguity, something familiar but distant, like a memory you’re not sure is yours. I’m interested in how much we can read into a body, even when the face is obscured or the context is unclear.

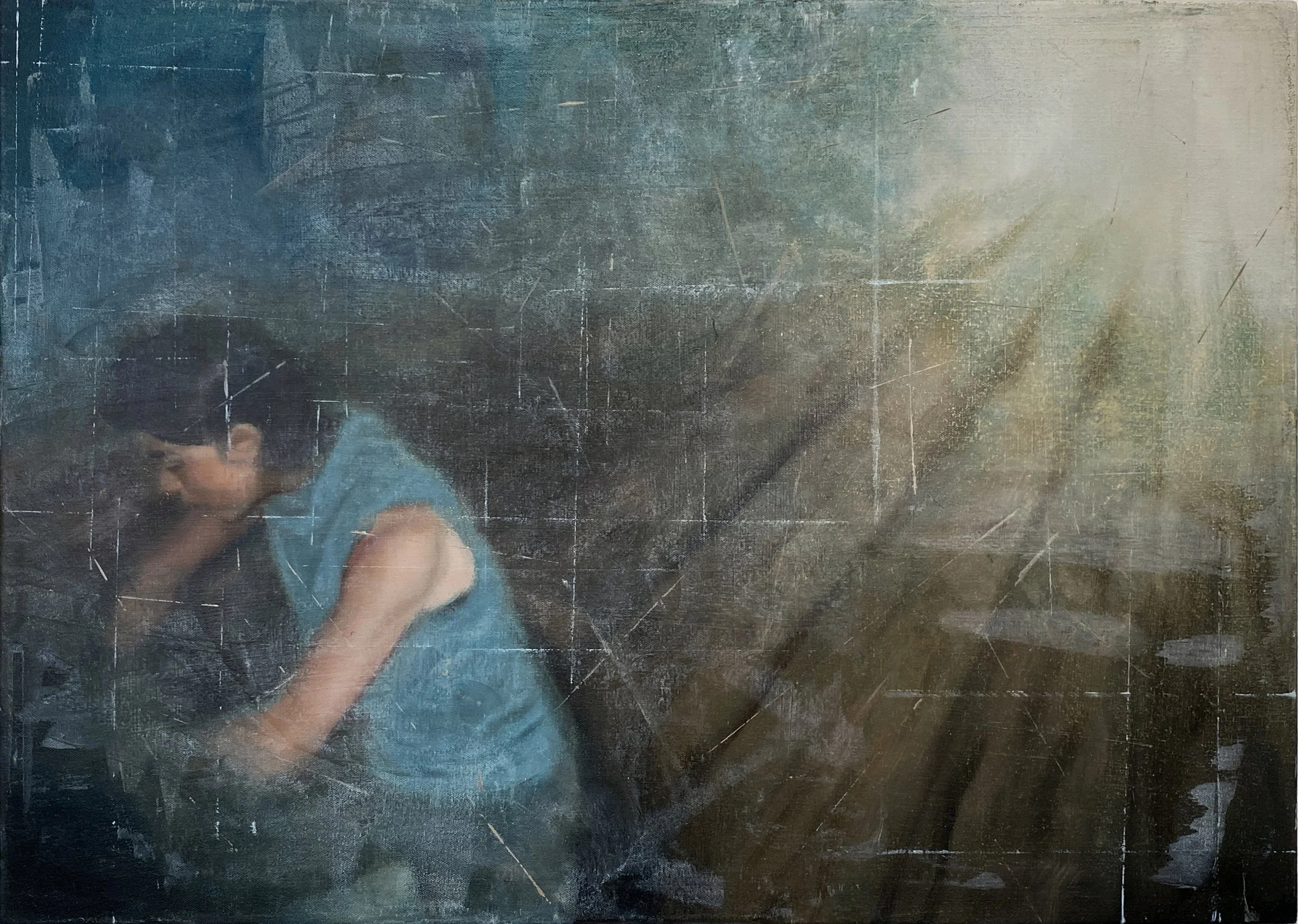

‘How Aeolian’

Despite being a young artist, at 24 you have achieved the BTA Young Artist of The Year award, as well as being selected as a resident of the Muse Gallery. What are your future aspirations? What do you envision for the future of your artwork?

I’m very grateful to have been selected as Behind the Artist’s young artist of the year, and being a resident at the Muse Gallery was an incredible experience where I learned a lot about my practice and met some amazing people. My aspirations for the future are that my work and the ideas behind it continue to evolve and grow. I’m always thinking, “What’s next?” when it comes to my work, and even as I write this, I have a new and exciting body of work planned and ready to be painted.

‘Jakob’

If you were given the opportunity to have a conversation with any artist; dead or alive, who would it be, and why?

I’d love to speak with Gerhard Richter. I’ve always been an admirer of his practice. His use of blur as both a formal and conceptual device has had a big influence on my own practice. I’d love to question him about the relationship painting and photography share in his work, and how he navigates the space between clarity and distortion in relation to memory.

Why do you think art is important in society?

Art is crucial in our society. It was Shakespeare who wrote, “Art is a mirror that we hold up to nature.” This continues to be relevant almost 500 years after he wrote it. It is the mirror we hold up to ourselves, even on a personal level, it helps us understand ourselves better. Art has acted as a therapy in my life, and I would encourage anyone to try it. I am at my calmest and most relaxed when I am painting (most of the time!).