ARTIST INTERVIEW: DEBORAH GRICE

Deborah Grice

What ignited your passion for art? Why did you decide to pursue a career as an artist?

I think, in truth, I never really had a choice about becoming an artist – it felt like art chose me. From a very young age, I had this instinct to search for truth, not just in a literal sense but in how the world felt and how it could be understood. I could draw naturally, and that ability was encouraged, but it wasn’t the act of producing a finished image that drew me in. What fascinated me was the process – investigating, questioning, and uncovering meaning through image making.

Looking back, it was less a matter of actively choosing art than of letting other possibilities fall away. I had interests in medicine, but painting was the one thing that remained constant. It became the way I could express things that couldn’t be spoken.

How do you evoke the feeling of nostalgia through your landscapes?

Nostalgia is central to my landscapes, though not always in an obvious or sentimental way. Stylistically, I’m influenced by 19th-century Romantic painters – both Scandinavian and British. Their ability to evoke atmosphere, longing, and memory resonates with me deeply.

The Nostalgic Future

Part of this stems from my own childhood. Growing up in rural East Yorkshire, I was always aware of how landscape carried both comfort and unease. There’s a familiarity in images we’ve all grown up with – like Constable’s Hay Wain on biscuit tins or trays – but behind that coziness lies a tension. My paintings tap into that duality: the safety of something known, but also the melancholy of memory, and the awareness of how fragile those feelings of belonging can be.

Our Truth II

Tell me about your fascination with geometric shapes. What inspired you to use them in your work, and how do they help convey emotion in your paintings?

Geometry has always fascinated me, probably because it was present in my family life from the start. My grandfather was an aeronautical engineer, and my father excelled at technical drawing. Growing up surrounded by tools, blueprints, and mechanical precision, I absorbed that visual language naturally.

But I was equally struck by how geometry jars when it collides with the organic. As a child, I remember looking at X-rays and being mesmerized by the intrusion of metal rods into bone. Out in the fields, I’d notice fences or bales of straw arranged into cubes and cylinders – unnatural geometry imposed on natural space. Those dissonances stayed with me.

A Tranquil Future

Later, when I gained my Private Pilot’s License, this fascination deepened. Flying gave me a completely different way of looking at the land – charts, navigation, and the geometry of flight paths all broke the earth into invisible grids and shapes that only a pilot would recognise. That aerial perspective sharpened my awareness of how geometric systems are layered onto organic environments.

In my work, geometric forms aren’t meant as symbols. Instead, they introduce emotional friction. A hard line or void cutting through a soft landscape can create a visceral sense of tension. These interruptions make viewers feel something bodily, not just visually – echoing the discomfort of when man-made structures intrude into organic life.

How have your surroundings influenced your artwork? Where do you feel most inspired to paint?

I grew up in a farming village in the East Riding of Yorkshire, and the countryside was woven into daily life. We’d spend time on the North York Moors or along the Yorkshire coast, places where the weather and the land shaped your every experience. That rural grounding made landscape painting feel like a natural path

Although my childhood sounds idyllic, it was shadowed by the omnipresent fear of nuclear war in 1980s Britain. My dad regularly took me to see the missile early-warning system, the “Golf Balls” at Fylingdales in North Yorkshire. Those incongruous, huge spherical shapes – which sadly no longer exist – left an early imprint on my imagination.

Later, during my time at Glasgow School of Art, I travelled to the Hebrides and discovered a new kind of wilderness. The islands had this raw solitude that seeped into me. Those moments of isolation, when you’re stripped back to yourself and the land, are still where I feel most inspired.

Thinking about your last piece, what was your creative process?

My process often begins in research – looking at Romantic painters of the 19th century, studying their use of colour, light, and structure. From there, I work on compositions in my sketch book. Once I move to canvas I sketch out the bare bones of the painting, then layering oils using glazing techniques to build light and atmosphere over weeks. Once this stage is complete, I photograph the work in progress and work digitally to refine the composition. This allows me to test those subtle dissonances – the balance between harmony and interruption, before committing them to the painting. Sometimes the additions take the form of houses, voids or lines. These interventions nudge the work away from purely a landscape into something more questioning and provocative.

Why are you keen to explore the idea of emptiness in your work, and how is this expressed in your paintings?

Emptiness is something I’ve felt since childhood, and it naturally weaves its way into my paintings. I was an unexpected twin therefore I have always had a feeling of being slightly outside of the family unit, which stayed with me as I grew older. Painting became my way of exploring that sense of distance and searching for belonging.

On a broader scale, I think contemporary society carries a form of loneliness. We are more connected than ever, yet many of us feel deeply unseen. My landscapes, with their expanses of wilderness and quiet voids, aim to reflect that collective ache. But equally, I want them to carry hope. Emptiness in my work isn’t just absence – it’s space for possibility, for viewers to project themselves and realize they are not alone in their feelings.

Where We Hope IV

If you could spend a day with any artist, dead or alive, who would it be, and why?

I can’t answer this without first mentioning my husband, Andrew Tyzack, who I met at the Royal College of Art. He’s not only a painter but also the person who has always encouraged me, constantly encouraging me back to the easel when my confidence is low, or researching techniques and pigments to help me develop my work. Any success I have is really half his! Beyond him, though, I’d choose two artists: J.M.W. Turner and Agnes Martin. Turner taught me that painting could be more than depiction – that it could embody weather, passion, and the very force of nature. Martin, in contrast, showed me the meditative and transcendent possibilities of painting. Her Arizona works shifted my practice almost overnight, opening me to new ways of thinking about space and rhythm. In many ways, I feel my work is the child of their two voices – Turner’s tempest and Martin’s stillness.

How do you envisage your artwork developing in the future?

I don’t think I’ve painted the work I’m truly proud of yet. Each day in the studio, I push toward that elusive image – the one that feels whole, balanced, and true. Painting is always a dialogue. Sometimes the canvas resists; sometimes it leads me somewhere unexpected.

I want to keep experimenting with modern pigments, refining my use of geometry, and pushing the tension between familiarity and unease.

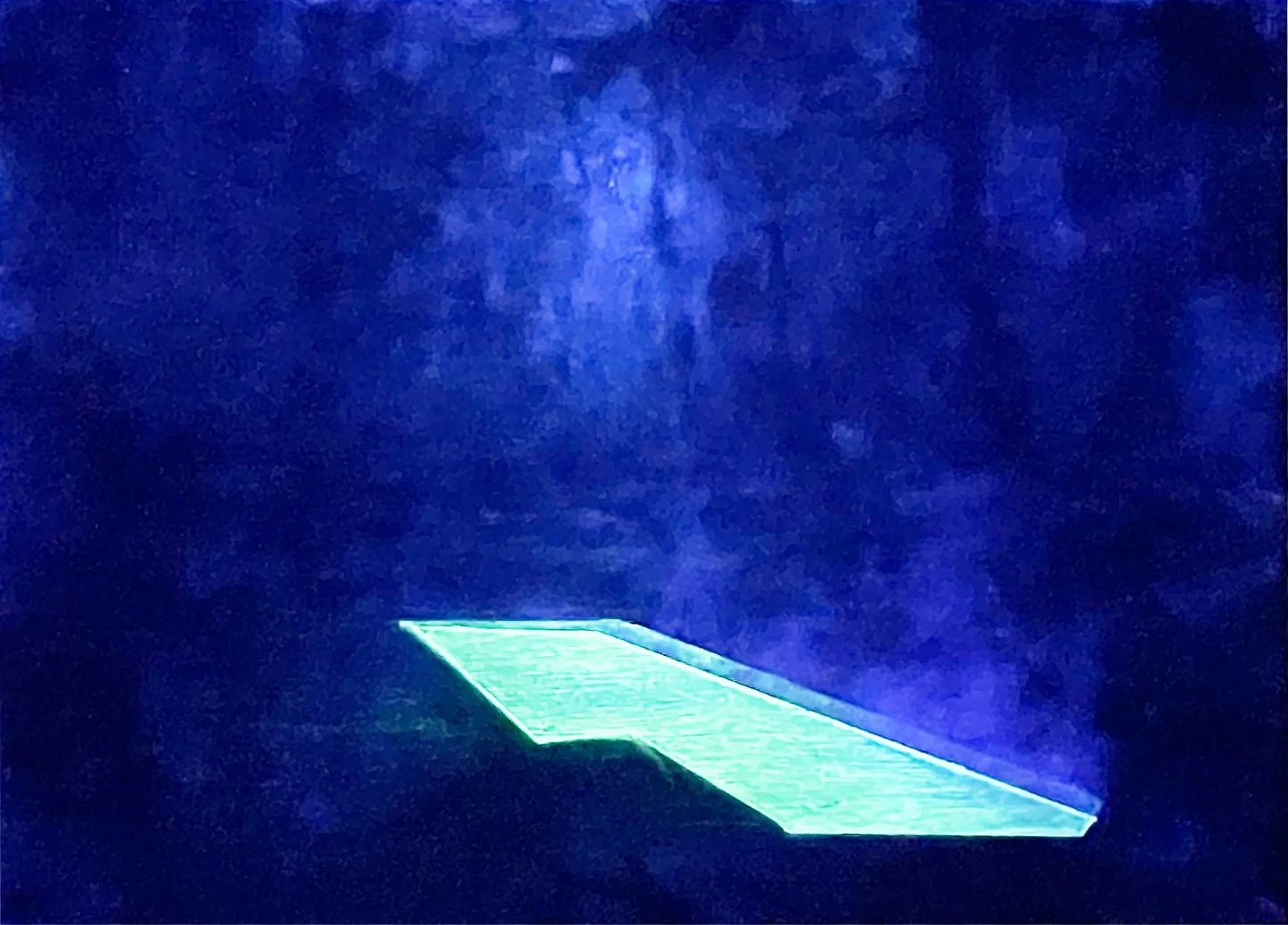

I’m honoured to have been shortlisted for this year’s ‘John Moores Painting Prize’ (2025) at The Walker Gallery in Liverpool. My painting ‘Safehold’ uses a phosphorescent pigment that glows in the dark. I spent two years developing a technique that allows me to combine this pigment with oil paint, creating a unified picture surface.

Even though I enjoy experimenting and pushing my work forward, what matters most to me is maintaining sincerity. I don’t want to echo or mimic others; I want my work to be authentic, felt, and lived.

Safehold

Why do you think art is important in society?

Art, in all its forms is vital because it communicates what everyday language cannot. It gives shape to emotions, to memories, to truths that might otherwise remain hidden. At its best, art creates those powerful moments of recognition: when someone sees or hears something and feels, these are my people.

Beyond that, art enriches daily life. It shapes the spaces we inhabit, informs design, and helps us live in environments that are thoughtful and aesthetically considered. Perhaps most importantly, it bridges differences. In a world often divided by ideology, art allows us to meet in a shared emotional space, revealing the values we hold in common.